Everything About Ringless Honey Mushrooms

Do not eat any mushroom without checking in person with a local, live, mushroom collector.

The first time I thought I saw the Ringless Honey Mushroom was on my neighbor’s lawn. The only problem was this species of mushroom grows on wood such as stumps or on decomposing roots. I had lived in the neighborhood 13 years and didn’t remember a tree on the lawn … though maybe there was a stump there when I first moved in…

Notice a slight raise and more dark hairs in the middle of the cap. The cap’s flesh is also white (see inside crack) to help you distinguish it from the toxic orange-flesh Jack-O-Lantern. Photo by Green Deane

Next time I thought I saw it was 200 miles away in West Palm Beach growing on an Eastern Cedar stump, or Southern Cedar … much the same thing (Junipers.) Ringless Honey Mushrooms usually don’t like conifers (its the pitch I imagine. I’ve also noticed them growing on Camphor stumps — pass — and on banyan roots… maybe worth trying as that is the fig family.) The third time, however, was a charm, about a mile from my house growing on oak stumps in an area that had been cleared a couple of years earlier. It was a mushroom mine, so to speak. When I took a Mushroom Certification class in late August in North Carolina they were everywhere. Locally they like October through December with November being the heaviest month.

Gills are widely spaced, touch but don’t run far down the stem, and stain or turn brown or brownish pink when bruised or aged. Photo by Green Deane

The Ringless Honey Mushroom, Armillaria tabescens, is a southern stand-in of a very common mushroom in North America and Europe, Armillaria mellea. which is also edible. The A. mellea, however, has a ring around the stem — an annulus — as almost all Armillaria do. The Ringless Honey Mushroom does not have a ring and there is also one ringless species in Europe, the A. ectypa. It is rare and classified as endangered in some areas. I note A. ectypa only grows in acidic marshes and is listed as edible and non-edible…. not good form to list an endangered species as edible. A. mellea is an infrequent Florida mushroom in the spring. Though looking similar again it has an annulus and the cap is tacky.

Ringless Honey Mushrooms grow on wood, in this photo around an oak stump. Photo by Green Deane

As mushrooms go the Ringless Honey Mushroom is one of the easier to identify. The Ringless Honey Mushroom grows on wood, preferably oak. But has also be found growing on Buckeyes, Hemlock, Hollies, Junipers, Sweetgums, Plums, Apples, Perseas, Maples, Pines, Ash, Alders, Almonds and Walnuts. Ringless Honey Mushrooms found growing on Hemlocks and Buckeyes are known to cause digestive upset. I would avoid those growing on plums, apples, almonds and hollies. Those trees can have some nasty chemicals in them including hydrocyanic acid. However a mycology professor told me these mushrooms should not pick up any bad chemicals from such trees. Oak is the most common and safest bet.

The spore print is white which helps separate it from the hallucinogenic Gymnopilus spectabilis (orange-brown spores) the deadly Galerina autumalis (brown spores) and Pholiota species (brown spores.) Photo by Green Deane

James Kimbrough in his book “Common Florida Mushrooms” says of the Ringless Honey Mushroom: “This is the most common late fall-early winter mushroom in Florida. It causes mushroom root-rot of numerous tree and shrub species, and is especially critical in the die back of oaks. It is seldom found in summer months, but appears in striking numbers as soon as late fall rains commence. It is a choice edible species, but because of its toughness, must be cooked longer than the average mushroom.” I would add one usually does not eat the stem. The mushroom is also a good candidate for drying. I fry them but have also parboil them for 15 minutes or so first, drain, then used.

Gills are knife-thin, sometimes forked, stems are white or light yellow on top tapering downward to darker stems. Photo by Green Deane

As for the scientific names, Armillaria (ah-mill-LAIR-ree-ah) is Dead Latin for “little bracelet.” Tabescens (tay-BESS-sins) mean decomposing. One would like to think it is called “little bracelet” because it can embrace an entire small stump but no. It is because of a bracelet-like frill on the fruiting bodies. And I don’t know if tabescens refers to helping wood decompose or the brown-black pile of dried muck the mushroom becomes when reproduction is done. They are called “honey mushrooms” because their color is similar to honey. And it should be added that not all categorizers of mushroom like “Armillaria” for the genus and prefer “Desarmillaria.”

Ringless Honey Mushrooms are cespitos, growing in a cluster. Also note how light-colored the young stems are. Photo by Green Deane

Kimbrough describes Ringless Honey Mushroom this way: Pileus is 2.5-10 cm, convex to plane, sometimes sunken at the disc with uplifted margins; yellow-brown with flat to erect scales. The lamellae are decurrent, somewhat distant, staining pinkish brown with age. Stipes are 7.5 to 20 cm long, 0.5 1.5 cm wide, tapering towards the base; off-white to brownish in color, lacking an annulus. Spores are white in deposit, broadly ellipsoid, 6.0-10 x 5.0-7.0 um, not staining blue in iodine. Basidia are clavate, 30.0-35.0 x 7.0-10.0 um, with four sterigmata. Normally I would translate those technical terms into plain English but with mushroom you should also learn the argot. But to give you an idea: The cap is one to four inches across, shaped like an upside down bowl to flat across the top with the edge turned up…

David Arora author of Mushrooms Demystified, describes the related Armillaria mellea as an edible spring mushroom then adds Armillaria tabescens is the same except no ring (annulus) and a dry cap. He provides more details:

Mature caps can range from two to four inches across. Photo by Green Deane

Cap: 3-15 cm broad or more, convex becoming plane or sometimes broadly umbonate or in age uplifted; surface viscid or dry, usually with scattered minute dark brown to blackish fibrillose scales or erect hairs, especially towards the center; color variable: yellow, yellow-brown, tawny, tan, pinkish brown, reddish-brown et cetra. Flesh thick and white when young, sometimes discolored in age; odor mild, taste usually latently bitter.

A young cap’s color is uniform without any brusing or aging towards brown-pink. Photo by Green Deane

Gills: Mushroom perfectionists can really rattle on about gill attachment, which are admittedly important. Start with the word F.A.D. Free, Attached, Descending. Gills are one of those three but there are nuances. Do they touch with an upward swing or square one? If they don’t attache the stem at al they are free. So these are “adnate” meaning square on to slightly decurrent (running down the stem some) or sometimes notched — half adnate; white to yellowish or sordid flesh-color, often spotted darker in age. Stalk: 5-20 cm long, 0.5 3(5) cm thick, tough and fibrous with a stringy pith inside; usually tapered below if growing in large clusters, or enlarged below if unclustered and on the ground; dry, whitish (above the ring in the A. mellea) soon yellow to reddish brown below and often cottony-scaly when very young. Spore print white 6-10 x -6 microns, elliptical, smooth, not amyloid.

Habitat: In small or massive clusters on stumps, logs, and living trees, or scattered to gregarious (occasionally solitary) on ground — but growing from roots or buried wood; common on a wide variety of trees and shrubs… on oaks trees the mycelium (mushroom roots) can frequently be seen as a whitish fan like growth between the bark and wood.

Whether young or middle aged select only firm caps for cooking. Stems are tough and fiberous. Photo by Green Deane

Arora says (of the A. mellea which he also says describes the A. tabescens) is eminently edible. Use only firm caps and discard though stalks (which are used for stock.) It is an abundant food source, crunchy in texture, and a very passable substitute for the shiitake in stir-fry dishes. The bitterness cooks out, but some forms are better than others. Arora recommends because of its various forms beginner should pick only those growing on wood.

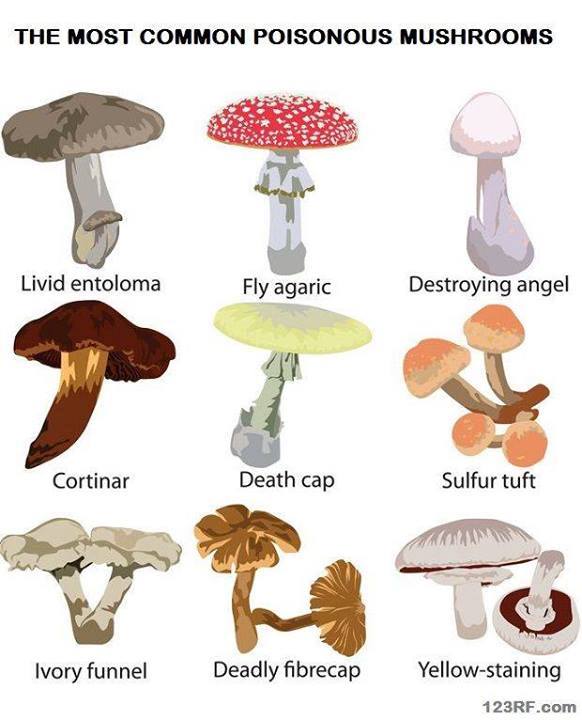

There are three or four similar-looking mushrooms which are toxic. The Galerina autumnalis has a ring, is smaller, and has brown spores. The Pholiota species also have brown spores. Gymnopilus have rusty-orange spores. The Sulphur Tuft, Hypholoma fasciculare, which likes to grow on wood, has purple-brown spores. That leaves Jack-O-Lanterns, Omphalotus.

Jack-O-Lantern mushrooms, above, look similar but the cap’s inner flesh is orange or yellow, not white like the Ringless Honey Mushroom. The Jack-O-Lantern can cause severe gastric distress.

“Jacks” are similar but in age can become vase shaped. More importantly their color is shades of orange or reddish-orange, occasionally yellow orange or one species olive orange. The cap is smooth, the Ringed Honey mustard has small black hairs. Also the gills run down the stem strongly whereas in the Ringless Honey Mushroom the gills meet the stem or run down only a little. The flesh of the Jack-O-Lanterns is about the same color as the cap whereas the Honey Mushroom cap is tan/brown and the flesh is white. If you’re healthy Jacks won’t kill you but will cause severe gastrointestinal illness. Fresh Omphalotus gills can glow faintly in the dark. I’ve seen this several times. As the mushroom ages it loses the ability to glow so don’t rely on it. Some folks mistake Jacks for Golden Chanterelles but Chanterelles when cut are white inside (like the Honey Mushroom) and do not have true gills but rather ridges.

From the kitchen of James Kimbrough: Mushroom Meatloaf.

Young Armillaria tabescens. Photo by Green Deane

2 pounds of Armillaria mellea or A. tabescens

1 Large onion

2 Tablespoons butter

1/2 Cup of dry bread crumbs

2 Eggs, lightly beaten

1/4 Butter melted

1/2 Teaspoon salt

Dash of pepper

Saute half of the onion in two tablespoons of butter until golden brown. Save several large mushroom caps for garnish. Chop remaining mushrooms, including stems and remaining onions; mix with bread crumbs, salt, pepper, and remaining butter. Stir in eggs and sauteed onions. Press entire mixture in a well-greased loaf pan. Arrange mushrooms caps on top and press slightly. Bake for one hour at 350 F. Let stand several minutes; slice and serve with mushroom gravy.

The post Ringless Honey Mushrooms appeared first on Eat The Weeds and other things, too.

Other self-sufficiency and preparedness solutions recommended for you:

Healthy Soil + Healthy Plants = Healthy You

The vital self-sufficiency lessons our great grand-fathers left us

Knowledge to survive any medical crisis situation

Liberal’s hidden agenda: more than just your guns

Build yourself the only unlimited water source you’ll ever need

4 Important Forgotten Skills used by our Ancestors that can help you in any crisis

Secure your privacy in just 10 simple steps

Do not eat any mushroom without checking in person with a local, live, mushroom collector. The first time I thought I saw the Ringless Honey Mushroom was on my neighbor’s lawn.

Cardiac Glycosides are most often found in Lily-of-the-Valley, foxglove oleander and squill. First signs include headaches, confusion, vomiting, stomach pain, and dizziness. Children might also experience changes in heart rate and blood pressure.

Cardiac Glycosides are most often found in Lily-of-the-Valley, foxglove oleander and squill. First signs include headaches, confusion, vomiting, stomach pain, and dizziness. Children might also experience changes in heart rate and blood pressure. The best thing parents can do for kids is to teach them never to pick or eat anything from a plant they find outside, regardless of how good it smells or looks. Make sure your children know to eat plants or fruits from outside only if they have permission and if the plant has been washed thoroughly.

The best thing parents can do for kids is to teach them never to pick or eat anything from a plant they find outside, regardless of how good it smells or looks. Make sure your children know to eat plants or fruits from outside only if they have permission and if the plant has been washed thoroughly.